Why Beauty Matters for Christian Education (Part 2)

Beauty enlightens us to truth and inspires awe.

“Beauty is essentially the object of intelligence, for what knows in the full meaning of the word is the mind, which alone is open to the infinity of being.”

—Jacques Maritain

In part 1 of this series, I explained why there is great theological support for Christian educators to implement the appreciation of beauty into their subject areas. Namely, God is the source of all beauty, and so the contemplation of beauty helps to point our hearts toward him.

In this essay, I will explain two additional reasons why this approach has great spiritual and educational value: (1) beauty enlightens us to truth and (2) it inspires awe and humility — both essential things for learning.

Beauty and Truth

Abraham Kuyper claimed that “the beautiful is not the product of our own fantasy, nor of our subjective perception, but has an objective existence, being itself the expression of a Divine perfection” (Lectures on Calvinism, Lecture V: “Calvinism and Art”). If true, this would mean there is an objective reality to beauty — a truth that we are grasping when we have an aesthetic experience. It would follow then that our aesthetic experiences are more than just emotional experiences, they involve our mind perceiving a type of knowledge.

This is essentially what Thomas Aquinas believed. In Summa Theologica, he said:

“Beauty relates to the cognitive faculty; for beautiful things are those which please when seen. Hence beauty consists in due proportion; for the senses delight in things duly proportioned, as in what is after their own kind — because even sense is a sort of reason, just as is every cognitive faculty.” (Summa Theologica, First Part, Q5, Article 4)

When Aquinas said “beautiful things are those which please when seen,” he did not necessarily mean that all beauty is of a physically visual nature. He meant ‘seen’ in the same way that someone ‘sees’ the truth in an argument, or when we say, “See what I mean.” There is a type of ‘seeing’ that our mind does when it grasps a truth. This is more likely what Aquinas meant. What, then, is the truth that our minds are seeing when we experience beauty? The inner form of things.

For Aquinas, we acquire knowledge when our minds apprehend the inner form of an object, artifact, or person. The inner form is the non-physical blueprint or design that gives a thing its structure, coherence, and character. The form is ‘seen’ through, yet conceptually distinct from, the material components that a thing is made of.

When we are moved by a beautiful song, for example, we are not moved merely by physical noises, vibrations. Rather, we are moved by the form that gave those noises their unifying structure and meaning — ie. the song composition. But the composition, while a real thing that exists, is nonetheless non-physical and distinct from the noises that the song is expressed through (ie. the performance or recording). That’s why a different artist can perform the same song through similar but different noises when they play a cover of it. The noises are different, but the underlying composition is still the same one that came from the original artist’s mind.

As Thomas Dubay puts it:

“The instruments of an orchestra sound together not simply through simultaneous noises with all their differences of qualities and notes and regular patterns, but only when a composing mind bestows on them a melodic unity, a radiant form.” (The Evidential Power of Beauty, Chapter 3)

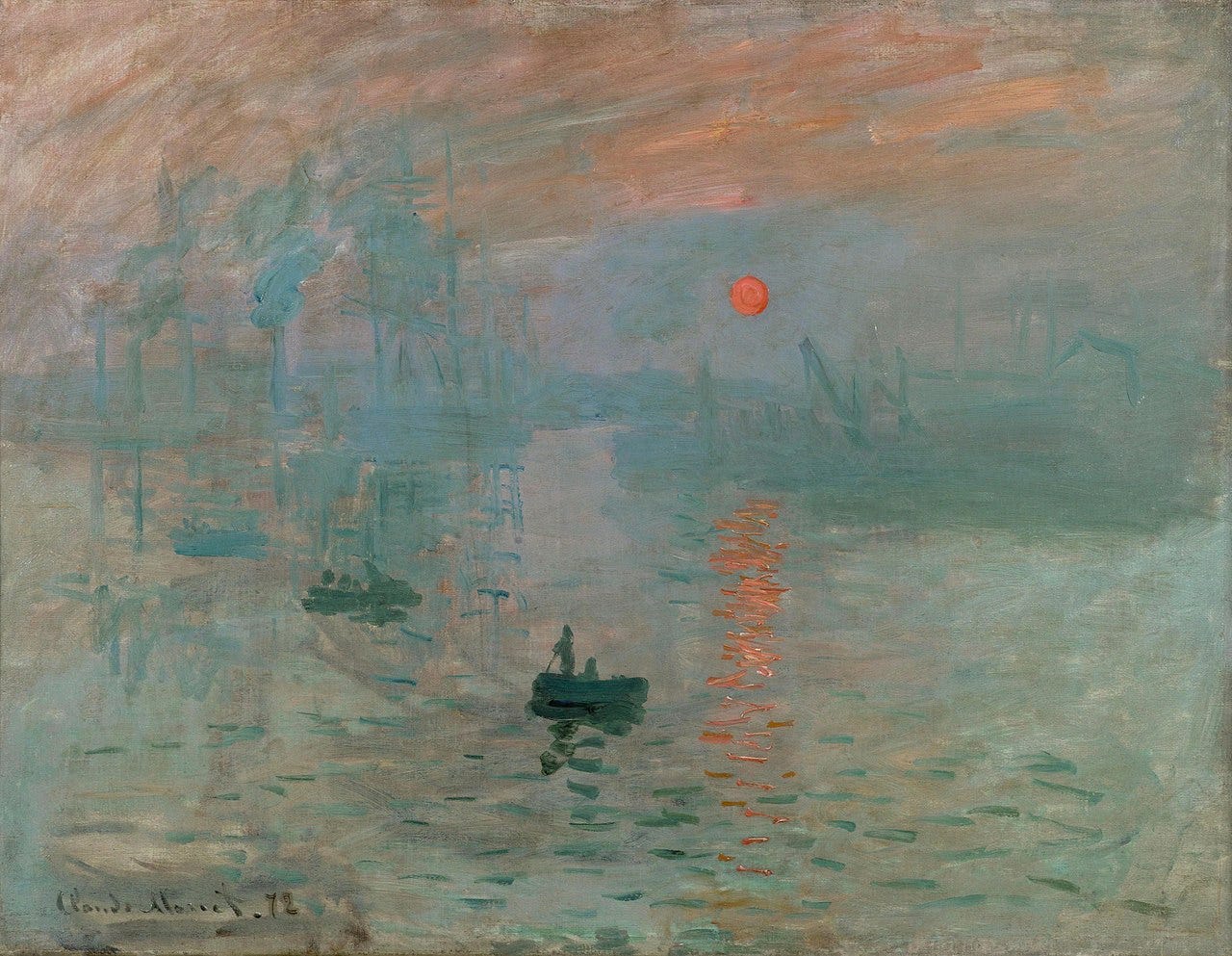

Visual art is the same as music. When someone is moved by Monet’s Impression, Sunrise painting, for instance, they are not moved merely by physical specks of color. Rather, they are moved by the form that gives those splotches of color their coherence and character. And in both cases of the song and the painting, the inner forms that captivate us originated from the minds of the artists.

When we have an aesthetic experience, whether it’s of a work of art or a work of nature, Aquinas would say that our mind is beholding the inner form of whatever transfixes us. If, as Calvin argued, “the elegant structure of the world serves us as a kind of mirror, in which we may behold God,” then human art is a mirror of the mirror. Whichever one we are looking at — nature or art — our mind is seeing the truth of God’s glory reflected to us.

Beauty and Awe

To ‘see’ the inner form of a thing often requires more than just a cursory glance, though; quiet contemplation can be needed, which takes time. This is why some people will stare at a painting for a while, or listen to a song several times through, before they really ‘get it.’ Paraphrasing the theologian Hans Urs Von Balthasar, Thomas Dubay explains:

“Beauty is perceived only from within…Von Balthasar has remarked that… ‘In order to experience its form, a person must become interior to the work [ie. object], must enter into its spell and radiant space, must attain to the state in which alone the work becomes manifest in its being-in-itself.’… This reveals how immensely important for growth in the spiritual life is the perception of the inner form of the beautiful.” (The Evidential Power of Beauty, Chapter 4)

Entering into the ‘spell and radiant space’ of a thing of beauty — ie. ‘seeing’ its inner form — may take focus and quiet contemplation, practices that Dubay says also help us grow spiritually. Distraction, self-focus, and short attention spans are the enemies of contemplation. It should be no surprise, then, that they are often barriers to aesthetic experiences as well. How often do we miss the beauty all around us, simply because we don’t pay attention enough to contemplate it?

Of course, sometimes beauty is immediately evident without any contemplation needed. A beautiful sunset, or the smile of a loved one, catches us at just the right moment and surprises us. Sometimes, the inner form of a thing or person is so radiant that it captures our attention and gives us a sense of awe. If Dubay is correct, these awe-moments are spiritual in nature and can become more frequent through practice. His argument appears to be corroborated by some current research.

A recent New York Times article interviewed Dacher Keltner, a psychology professor at UC Berkeley, on awe-experiences:

“Awe…is the absence of self-preoccupation. This, Dr. Keltner said, is especially critical in the age of social media, ‘We are at this cultural moment of narcissism and self-criticism and entitlement. Awe gets us out of that.’…The good news? Awe is something you can develop, with practice.” (The New York Times, “How a Bit of Awe Can Improve Your Health,” 2023)

Awe is a form of humility — a tacit acknowledgement that we are not the center of the universe. Humility is a needed quality for education. To learn anything, we must first accept the fact that we need instruction and correction. If we are not open to that possibility — if we believe our perspective is always right — then we will not learn much. Arrogance is stupidity. Beauty, and the awe that it evokes in us, can be an antidote to our pride. As the Proverbs tell us, “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge” (1:7).

Beauty has the potential to cultivate in us a form of other-centeredness, the opposite of self-centeredness, and to mitigate our tendency toward pragmatism. The late Tim Keller put it well:

“When something is useful you are attracted to it for what it can bring you or do for you [eg. self-centered]. But if it is beautiful, then you enjoy it simply for what it is. Just being in its presence is its own reward [eg. other-centered].” (The Reason for God, Chapter 14)

Beauty and Education

If all of the above is correct — if, as Aquinas said, beauty engages the mind with truth, and if, as Dubay argued, the practice of ‘seeing’ beauty encourages habits that help us to grow spiritually, and if, as Keltner explained, awe is an antidote to self-preoccupation — then the value of implementing beauty in the classroom should be completely obvious. The more students are able to practice ‘seeing’ beauty, the more of God’s glory they will encounter, and the more awe and spiritual humility they will experience. To put it simply, they will learn more.

In the next article in this series, I will explain the final reason why Christian educators should incorporate the appreciation of beauty into their lessons when possible: because it deepens our understanding of scripture. My next few articles will be related to this series, and will offer some resources for a classroom setting.